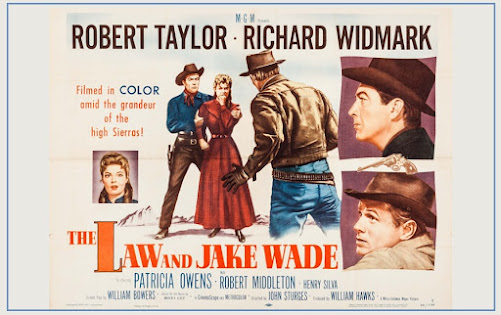

The Law and Jake Wade (1958)

John

Sturges is the director of two of the most popular westerns in history, Gunfight

at the OK Corral (1957) and The Magnificent Seven (1960). They're no doubt fine movies, but some of his fans (and I'm one of them) prefer his

'smaller' efforts, such as the Freudian noir-western Backlash (1956), the taut

cavalry versus Indians drama Escape from

Fort Bravo (1953) or the movie discussed here, The Law and Jake Wade.

Robert Taylor is Jake Wade, a reformed outlaw, now a town Marshall. His

personal code of honor tells him to save the life of his former partner in

crime, Hollister (Richard Widmark), who's about to be hanged in another town.

Hollister had saved his life in the

bad old days and Wade now considers the score settled, but Hollister has his

mind on the loot from their final heist, that was buried by Wade before going

straight. Hollister re-unites

with his gang and forces Wade to lead them to the place where the money is

buried. To make sure Jake cooperates, Hollister also captures the Marshall's bride-to-be

(Patricia Owens). The journey leads through Comanche territory to a ghost town

in the desert, where Wade has buried the money in the cemetery. Upon their

arrival in town, they discover that they were trailed by three Comanche scouts.

Hollister kills two of them, but a third one escapes ... and at night, the

Indians attack ...

The Law and

Jake Wade tells a rather familiar western story about former partners now operating on different sides of the law, but Taylor and Widmark are ideal

opponents and Sturges' direction is both economical and assured. Taylor is a perfect illustration of Sturges' ideas

about the western hero as a silent person, a God in his own universe who

resolves his issues with his gun (*1). No wonder most of the talking is done by

the villain, wonderfully played by Widmark.

The supporting actors are very good too, notably Henry Silva, as a sexually

frustrated young man with a Freudian father complex and Robert Middleton as the

good-natured gang member with a loyalty problem.

We learn

that Wade decided to go straight because he (erroneously) thought he had shot a

child during their last robbery, but otherwise the script, by William Bowers

(based on a novel by Marvin H. Albert) isn't over-explicative; snippets of dialogue - such as the two

men discussing if the other one would do the same thing if the odds were

different - inform us about their relationship: they were both part of a Confederate guerilla band during the Civil War and just turned to robbery after the war was over. It transpires that Wade never really liked Hollister but still felt responsible for him, because he realized Hollister was a psychopath.

|

| John Sturges |

The film is

not without flaws; there are a few jarring studio scenes, mainly of the group

gathered around the camp fire, and some have criticized the Indian attack for

being unrealistic and needlessly clichéd; the Comanche mainly climb on rooftops or ride through the town

street to be picked up by the people inside the ramshackle buildings. But the

arrows go "zing" and the spears and tomahawks fly around, plunging

into walls right beside people's heads, evoking that old feeling of excitement

we experienced when we were watching these cowboy & injuns movies as kids

(and reenacted the attack later in the backyard).

Notes:

* (1) In the book Peter Bogdanovich on the

Movies, Sturges expressed his views on the genre:

"Western characters must not be glamorized. (...) You can't make a Western

if it's pretty. (...) Always use a lot of back lighting, and don't let the star

talk too much. John Ford, you know, made John Wayne a star by not letting him

talk. But the absolute must for a Western is isolation. The man must be God.

And you've gotta take issues that can only be resolved by guns."

A great write-up of a great film - thanks! Some very useful references there.

ReplyDeleteWhat struck me about this film was that it's the only Western I've seen which is set in winter and noticeably cold - they have to wear heavy coats and gloves and there's snow on the peaks. Are there others set in winter that you know of?

The Italian western The Great Silence is famous for its snow-setting; and then there's Day of the Outlaw: http://westernsontheblog.blogspot.be/2013/10/dir-andre-de-toth-cast-robert-ryan-burl.html

DeleteThanks! I'll try and look them up. If one of them is de Toth it should be OK, I think. I love this film, not just that Widmark is such a great baddie, but the lovely scenery. Often to describe a film as having great scenery is to pay a backhanded compliment, suggesting perhaps that the acting isn't up to much but that's certainly not the case here.

Delete